Eleanor's Top Ten Hauntings of All Time | #7 The Cock Lane Ghost: Stop it, It's Not Funny

If you think being a comedian on the internet is hard, try being a ghost in 18th century London

In honour of my Fringe Show Haunted House, I’m doing a top ten real life hauntings run down, and this week its the not-so-sexy tale of the Cock Lane Ghost - a scandalous affair involving tabloid exploits, Hogarth, and rude names.

My first recollection of reading about this case came once again from Colin Wilson’s True Ghost Stories, and as a ten year old it took me a bit of time to wrap my head around the rather EastEnders-esque plot. There are lots of characters, two Elizabeths, a couple of marriages, one of them fake, and a confusing amount of money changing hands, but I think its important to the ghostly aspect of the narrative to understand the background of the players. This article was very helpful in reminding me of the particulars. What happened is as follows;

Our story takes place in 18th century Cock Lane, London. The origin of the name Cock Lane is a bit hazy - either it was a place where poultry was traded in the middle ages OR it was the site of a lot of brothels. Either way, the name is appropriate.

In 1760, Richard Parsons, a parish clerk, of Cock Lane rented out one of his rooms to a William Kent of Norfolk. So far, so London. Kent (that’s the man not the place) of Norfolk (the place, not a guy) had been married to one Elizabeth Lynes, but she died in childbirth, the child itself passing away two months later. The Kents had lived in the village of Stoke Ferry, with Elizabeth’s sister Fanny (grow up), who had come help look after the baby (not an uncommon practise at the time.)

Soon after Elizabeth’s death, Fanny and William began a relationship, which is, yes, pretty yuck. It’s not even as if they had the excuse of rearing the baby together. Records don’t seem to state Fanny’s age, but we can assume she was fairly young, and the whole thing has a slightly grubby vibe. Kent did want to make an honest woman of Fanny though - but he was told that marrying his dead wife’s sister was verboten (as Elizabeth had borne him a child, a union with her sister was viewed as incest).

By 1759, Kent was now in London (the man, Kent the place is in Kent, ok I’ll stop) attempting to put the whole palaver behind him. Fanny, desperately in love, followed him there, and he (apparently against his better judgement) agreed to let her live with him as man and wife. To be fair to Kent, he was trying to do the right thing (or at least appearing to). Although the Georgians were more laissez faire about sex before marriage than the Victorians would be, any children he and Fanny had would have no rights as his children, and would likely be shamed by society for their illegitimate birth. Since there was no real way to remedy this, breaking up altogether seemed the wisest course of action, but the headstrong Fanny would not accept it.

Georgian London - think less Bridgerton trysts and more syphilis, pre-marital hijinks and weeping sores.

Kent and Parsons met by chance at church one morning, and Parsons agreed to rent the young couple a room, no judgement. In fact, Parsons couldn’t really afford to be judgy - he was known as a bit of a drunk, always in need of money, and soon ‘Mr and Mrs Kent’ were lodging with the Parson family, which consisted of Richard, his wife and his two young daughters. The house in Cock Lane was a three storey building, with one room per floor, and a narrow stairway connecting them, fairly typical of older London streets of the time.

Kent then did Parsons a favour in return, lending him 12 guineas to be repaid one at a time. This is where the story always lost me as a child - if your landlord owed you money, wouldn’t you simply not pay them rent? Anyway, I digress. The scene is set. A respectable parish clerk always teetering at the edge of ruin, the scandalous Kents, and last but by no means least, Parsons’ 12 year old daughter, Elizabeth.

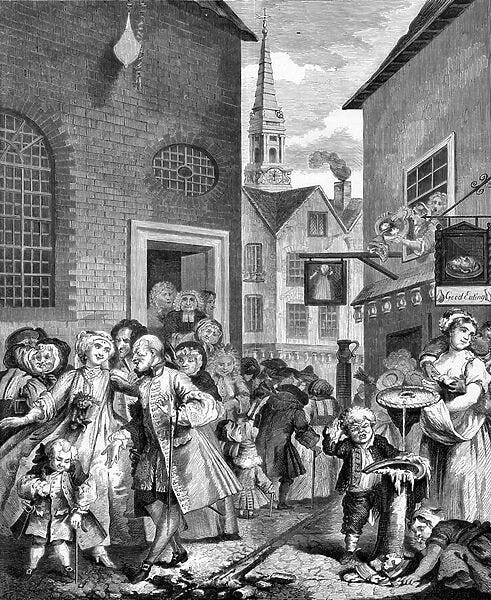

Another Hogarth Print - Four Times of Day, Noon, depicts Georgian London as a busy, bustling, noisy and crowded place to live.

The ‘Ghost’ first appeared whilst Kent was away. Fanny had asked Elizabeth, the daughter, to share her bed whilst Kent was away. This might seem a bit weird to us now, but separate beds and bedrooms are a more modern concept than we think. Servants would have usually slept in their masters rooms, on ‘truckle beds’ and Fanny, like many other women, may have wanted someone else present to dissuade any male night time visitors. Fanny was also pregnant, and probably needed someone keep an eye on her.

Elizbeth and Fanny began hearing scratching and rapping noises (a classic sign of an early poltergeist manifestation) which they could not account for. It didn’t seem to come from neighbouring shops (Cock Lane had lots of workshops and would have been very noisy) and one by one neighbours trooped in to listen to the noises. The first thing that most people think when they hear ‘scratching noises’ is rats - how could it be anything else? But assuming that Georgians would know exactly what a rat sounded like, we can take it for granted that these noises were different enough to freak out Fanny and her 12 year old charge.

The noises continued, and a neighbour and Parsons both claimed to see a figure in white in the house, with the cobbler seeing it on the stairs.

What appears to be a clergyman (probably Parsons) witnessing an apparition who seems to be glowing (and about 7 feet tall). The giant, Ikea-kitchen-style clock points to midnight

Once Kent returned, however, and Elizabeth went back to her own room, the noises apparently ceased. Not long after, in January 1760, the Kents moved out in order to prepare for the arrival of their baby, but Fanny fell ill and was diagnosed with smallpox, dying in February 1760. After her death, the Lynes family discovered that Fanny had left almost everything she owned to Kent. The Lynes were not happy, and started proceedings against Kent, who was already remarried by 1761.

All was quiet in the Parsons household (at least, in terms of ghosts) until 1762 when, just as Kent himself began proceedings against Parsons (who still owed him money) the scratching noises started up again. Another lodger moved out after being unable to stop them, and the wainscotting around Elizabeth’s bed was even removed to try and locate a source for the noise. Elizabeth, like most tweens in poltergeist tales, was acting up, and appeared to have fits as well as be a conjugate for the noises.

Once again, the mysterious noises began to attract attention - this time with a juicy caveat - could the original noises have been the ghost of Elizabeth Lynes (Fanny’s sister) warning Fanny that a life with Kent was doomed? And had Fanny herself now returned to tell the Parsons something about her untimely death?

More and more visitors flocked to the house. Seances were held, experiments done, and ‘Scratching Fanny’ became the talk of the tun. (They say that in Bridgerton, right? Am I doing it? Am I doing popular content?).

Of course, it won’t escape the modern reader (or any reader after the mid 19th century) that a ‘scratching Fanny in Cock Lane’ is quite the mental picture. Some people speculate that ‘Fanny’, the women’s name, took on its slang meaning (in UK English, a vulva) after the 1748 publication of Fanny Hill, about a sex worker’s exploits in London, but we can’t be sure people around the time of the ghost would have used it that way. Cock, on the other hand, definitely had its meaning firmly, ahem, rooted by that point. Either way, the talk of premarital sex, death and impropriety gave this story a seediness that delighted the British public, regardless of the names. Cock Lane was overrun with the coaches and horses of the great, the good, and everyone in between, all clamouring for an audience with Scratching Fanny Herself. Parsons began charging people to enter, claiming that he needed the money since he could no longer rent his rooms. Hmmmm.

One of several depictions of the Cock Lane ghost at work - here men check under the bed, women pray, and the children (who appear to be babies here) are the centre of the phenomenon. On the wall are prints of two recent hoxes - the kidnap of Elizabeth Canning, and the Bottle conjuror, suggesting the artist doesn’t take this haunting too seriously.

Parsons approached assistant preacher John Moore at his church, St Sepulchre, for help. They devised a system which would be used in other ghostly encounters to come- one knock for yes, two for no. With this morse code in place, they asked the ghost to explain itself, and the ghost came out with an extraordinary tale…it claimed to be Fanny, telling them she had been murdered by Kent, who had given her arsenic mere hours before her death. All of this rapping, of course, took place within the presence of the young Elizabeth Parsons.

This scandalous revelation was huge, and Kent himself soon got wind of it. He demanded vindication, whilst Elizabeth Lynes sister Ann demanded to see her body, which would indicate her true cause of death.

Elizabeth Parsons was thoroughly (some would say too thoroughly) examined - undressed in front of a crowd, being strung up in a hammock, having her arms and legs held, and it was discovered the knocks would not manifest when she was held, or completely visible to spectators. She was also sent to stay in other houses, where the noises sometimes followed her, and sometimes stayed behind in Cock Lane. Eventually, after being threatened with Newgate prison if the knocks did not manifest, she was caught with a piece of wooden board in her bed, more or less confirming for sceptics that the whole thing was a hoax.

Ooooooooooo - It’s a bit of wood!

Meanwhile, Kent was insisting his innocence be proved once and for all. On 25th of February, 1762, Kent, the parish priest, sexton and several others, went down to the vault where Fanny was interred. With baited breath, they prised open her coffin lid, only to discover, to their horror…the corpse of a woman who had been dead for two years. Yup. Just a dead body. No signs of poisoning of foul play. Gross.

You know a prank has gotten out of hand when they’re digging someone up.

And so that was that. Well, almost. It turns out unfairly accusing someone of murder is slander, whether you’re a ghost or not, and so Parsons, his wife, John Moore and several others were all charged with conspiracy. Kent and his supporters proved that Fanny was ill with smallpox, not poison, and that the noises heard before she died were considered by many a hoax. John Moore, who seems to have been the most honest about his part, said that although he did not cause the noises, he had no idea who did and whether they were really supernatural. Most of the defence witnesses seemed really to believe that the noises were made by unseen forces. Parsons and the others were all found guilty and had to pay Kent several hundred pounds (lot of money in them days). Parsons was also sentenced to be pilloried (i.e. put in the stocks, which, unlike in American fantasy movies where people throw tomatoes and other New Word veg, was actually a horrible and highly dangerous experience. Dying in the stocks from abuse or injury was not uncommon). Luckily for Parsons, the community took his side, and he was protected from abuse by neighbours.

The Cock Lane ghost is perhaps the least ghostly of all the haunted houses featured. Actual apparitions were sparse, the hoax seems pretty obvious, and a majority of the people following the case at the time did not seem to take it seriously.

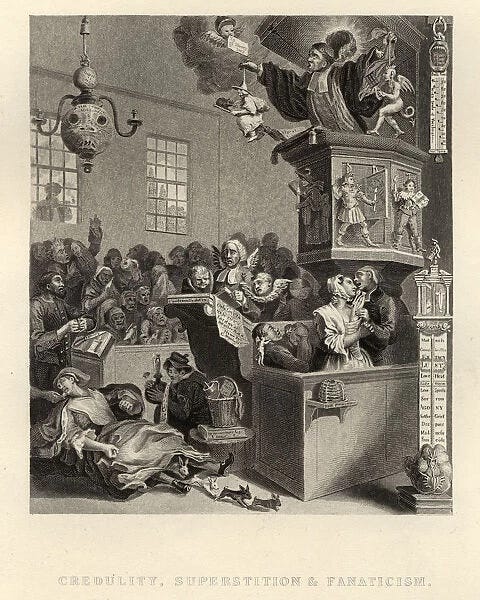

Yet it remains fascinating for several reasons. Firstly, as an incredibly well documented example of a haunted house. Few cases in history have so many witnesses, documents and testimonies to their name. And it also carries the glamour of celeb - some of the witnesses and interested parties included figures like Horace Walpole, Samuel Johnson, the Duke of York, and of course, William Hogarth, who created numerous etchings about the case.

Cock Lane serves as a perfect showcase of many Georgian fears, interests and beliefs: Methodism vs Anglicanism, celebrity writing and publishing, science vs superstition, and an obsession with weird and wonderful ‘true’ stories, such as Mary Toft, the woman who claimed to give birth to rabbits. Just as today, Georgians were constantly clamouring for the next big story, and many people were eager to get their 15 minutes of fame.

Perhaps most notably, it was used as an example by satirists like Hogarth of the ways in which the British public were not the enlightened thinkers they considered themselves to be. At the height of the Age of Reason, the fact that thousands could have been fooled by a 12 year old girl and a bit of wood must have been an embarrassing stain on the British psyche.

There are also uncomfortable messages here about the treatment of girls in Georgian society. Elizabeth Parsons, barely a teen during the case, was prodded poked, violated, deprived of sleep and abused in many other ways by adult men in this case, and no one seems to have commented on the inappropriateness of this. Like in the later case of The Salem Witch Trials, female children were at once taken seriously in their cries of ghost, and at the same time dismissed as mere objects without agency. Was it all Elizabeth’s fault? Or the fault of the many, many esteemed adults who took her seriously, and the father who potentially exploited her?

Lastly, I think the Cock Lane ghost and its seedy undertones remind us what humans really care about: money, sex and status. The noises did not really ramp up until Kent went after Parsons for the substantial amount of money he owed, and I think this says a lot about the true priorities of the so-called Cock Lane Ghost.

One of the most famous artworks depicting the ghost, by Hogarth: the Cock Lane Ghost can be seen at the top of the thermometer on the right, which apparently measures types of human madness. Mary Toft is on the floor, pushing out bunnies.

Next time: A Haunting at a Jamaican Plantation may be myth, but reveals some very real horrors…

Liked this? Support me on with the price of a coffee here or buy a ticket to Haunted House!