Eleanor's Top Ten Hauntings of All Time | #10 Mary King's Close, My Own Personal Nightmare

We're getting personal with the last haunted house in the series

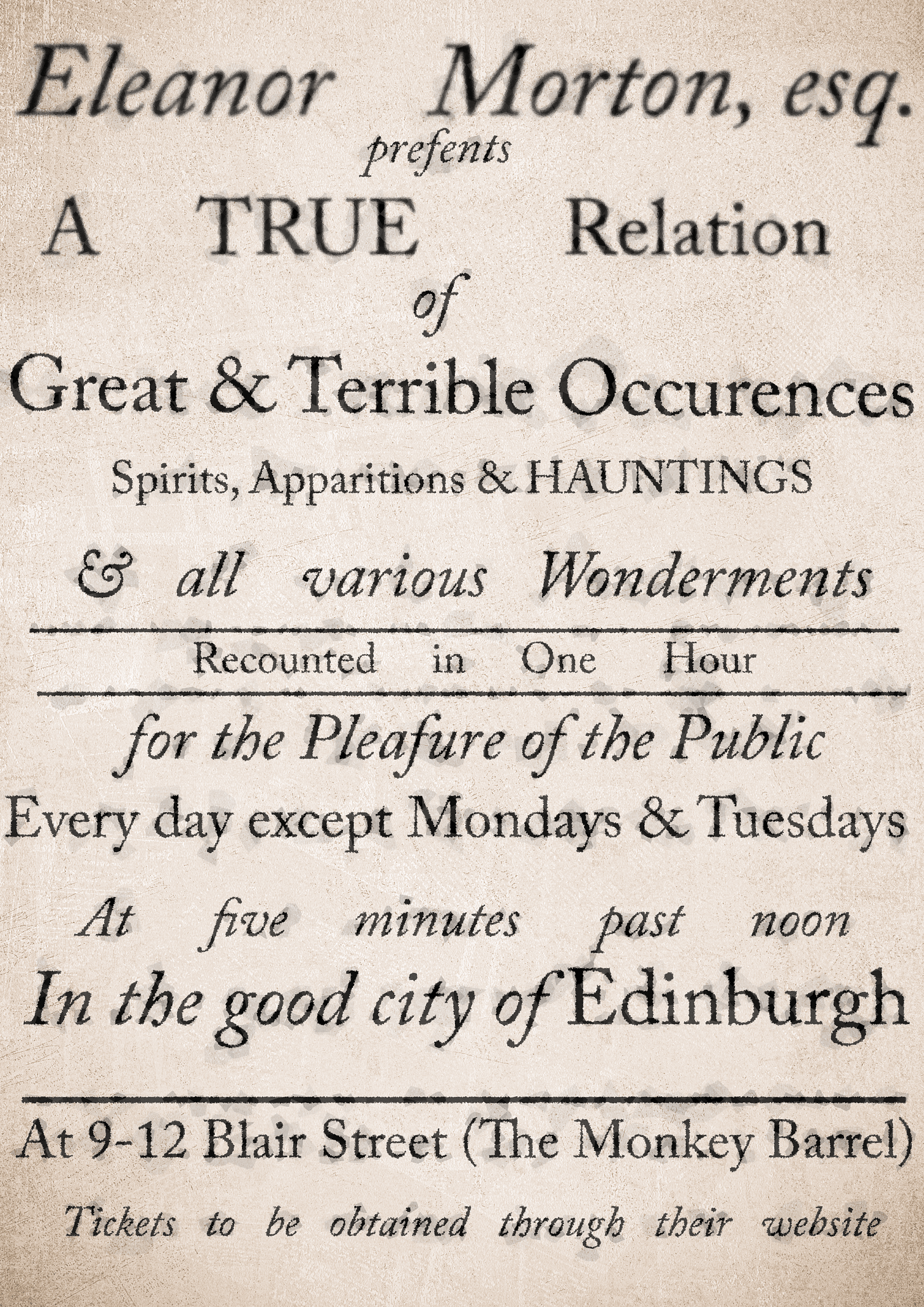

In honour of my Fringe Show Haunted House, I’m doing a top ten real life hauntings run down, and for the last instalment, I’m going local.

When I was in primary school, aged maybe 8 or 9, we did a ‘history of Edinburgh’ project. It’s fairly standard in UK primary schools to do a project on your home town and its past. Edinburgh has been a settlement for thousands of years, and my primary school was on the site of Roman ruins (our school badge was a Roman ship). What made our project different from most, however was how dark and horrific Edinburgh’s history is. I can say with absolute confidence that it was a traumatising experience. Every city and town in Britain has a dark side, but Edinburgh seemed to be entirely constructed of them. Plague. Invasions. Beheadings. Hangings. Witch burnings. Murder. Body snatching. Open air prisons. Free flowing sewage. Poverty. Even our own queen, Mary, witnessed her husband and his cronies stabbing her friend David Rizzio to death. The hand drawn cover of my own project (which I’m trying to find!) included a witch being burned at the stake (contrary to popular belief, witches were usually strangled before death, burning alive was usually reserved for heretics in places like England) and a man being hanged. And those are just Edinburgh’s provable horrors - they have nothing on the myriad myths, legends and ghost stories that have sprung up over the centuries. How about the tale of the violently insane Marquess of Queensberry, who allegedly killed and spit roasted a kitchen boy in 1707? Or Major Weir and his sister Grizel, who were executed for worshipping the devil and partaking in incest? Or the plague fields that became the Meadows, a picturesque park full of cherry blossom?

The culmination of this primary school project, after a visit to the more historically sound Gladstone’s Land was a trip to Mary Kings Close. Nowadays, Mary Kings Close is fully open to the public - it has tour guides, exhibitions and a gift shop. In the early 2000s however, Mary Kings Close was nothing more than a series of abandoned streets and rooms under the City Chambers, Edinburgh’s council building on the High Street (or Royal Mile, as its more commonly known). It was inaccessible to the public, and you had to get permission to enter (and a key) from the council. A student from Edinburgh uni would then show you round for free (well, a tip). There was no lights, no information boards, no definitely no café.

An 18th century depiction of the Old Town, looking down from the High Street, with the Castle behind us. Mary King’s Close is towards the back on the left, roughly opposite St Giles (the kirk with the tower)

As a young child I found it hard to wrap my head around the idea that there were streets below the streets. I knew from the project that Edinburgh had been built on top of itself (fear of invasion meant all building work for several centuries took place within the very narrow confines of the city wall) but I couldn’t really picture it.

I remember entering the building, from an inconspicuous side door on Cockburn Street, and being taken into the labyrinth of rooms and tunnels. Our guide, who was probably only about 20 but seemed much older to me, then proceeded to relay a series of horrifying tales about the Town Below the Ground. There was Annie, the ghost child who haunted one of the rooms, and for whom several dolls and stuffed animals had been left. There was the poor chimney sweep boy who became trapped up one of the close’s narrow chimneys and starved to death. His bones were only recovered years later, and his pitiful cries for help still echo throughout the halls. Then there was the couple who moved into the close on very cheap rent, after it had been used to store dead plague victims, and who became haunted by floating, dismembered body parts which eventually chased them from their new home.

I couldn’t sleep for weeks after the visit. I became convinced that, if I closed my eyes, my suburban bedroom would somehow morph into the close, and there I would be, trapped under ground. My nightmares were so bad I vowed never to set foot there again. Of course, as I got older, the fears died away, and I have been back to the now much more commercially appealing Mary King’s Close in recent years. But I can never forget just how much terror my initial visit instilled in me.

So, what’s the real story of Mary King’s Close and its ghosts?

First of all, the name of this ‘underground city’ needs unpacking. A ‘close’, in the Scots language, is a narrow street akin to an alley. It can also refer to the stairway inside a tenement building, or even a full sized street. Most of the closes off the High Street are named either for the trade its associated with, or a specific person who lived there - for example, Fleshmarket Close (meat industry) Old Fishmarket Close, Advocates Close (originally leading to the house of the Lord Advocate), Bakehouse close, etc etc

Mary King’s Close, therefore, was named after Mary King, a woman who lived in the close in the 17th century, and who’s family were long associated with the area. Naming a close after its inhabitants was an easy way of locating people and businesses if you couldn’t read a map, or, in this case, a way of commemorating them.

The Close itself was built sometime in the 16th century, with more buildings and alleys being added over the next century or so. According to this website, Mary Queen of Scots stayed in a house in the close belonging to the Lord Provost Sir Simon Preston, on her last night in Edinburgh in 1567, before she was taken as a prison to Loch Leven castle.

The Close, like all of Edinburgh’s streets, would have been noisy, crowded and full of life. There would have been family homes, businesses and trades like butchers, shoemakers and even livestock all squeezed into fairly compact spaces. Even class would not have separated folk much - there simply wasn’t enough room for anyone but the very rich to remove themselves from the general population, and so middle classes and working classes would have lived practically side by side.

So why was the Close so cramped? Well, as mentioned before, Scotland was under constant threat of invasion from the English, and almost everything in Edinburgh was built within the city walls - which basically only extended down and around the High street. Think of it like a spine with each close and wynd as a rib - there was nowhere else to build, unless you wanted to expose yourself to attack outwith the city’s walls (which still exist and which you can see at various points in the old town, stretching all the way to Heriot’s School).

As well as this, the northern side of the city was bordered by the Nor Loch (North Lake), now Princes Street Gardens. ‘Loch’ was a generous description; it served as the city’s drinking supply, sewers and dump.

This etching of Edinburgh from above shows the ‘spine’ building plan, running from the castle at the top to Holyrood palace at the bottom. Mary King’s Close is roughly opposite the Kirk on the upper half of the page, (north) just above the Nor Loch.

Life in the Close would have been hard. As well as poverty and fear of invasion, Edinburgh, like most towns in Europe during the Early Modern Period, was visited numerous times by plague outbreaks, the most recent and serious of these in the 1640s. There was no cure for the plague (probably bubonic) and fear and superstition around the disease would have been high. It would have smelled pretty bad, been dark and damp, and overall, not Edinburgh’s premium destination.

One enduring myth about the close is that it was bricked up with living plague victims still inside, and these victims were left to starve to death, their wails and cries for help unheeded. As sensational and gruesome as this story is, its not true. People would have been quarantined to their homes, but they were not bricked up, and were visited regularly and fed by plague doctors (not that they could do much).

In 1760, the close was partially demolished and buried by the building of the Royal Exchange (now the city chambers) and became a warren of underground rooms and buildings.

(Some of this info is from Wikipedia links to an archived post from the MKC website, which shows that back in 2011, adult tickets were £12.95 - they’re £25 today!!!)

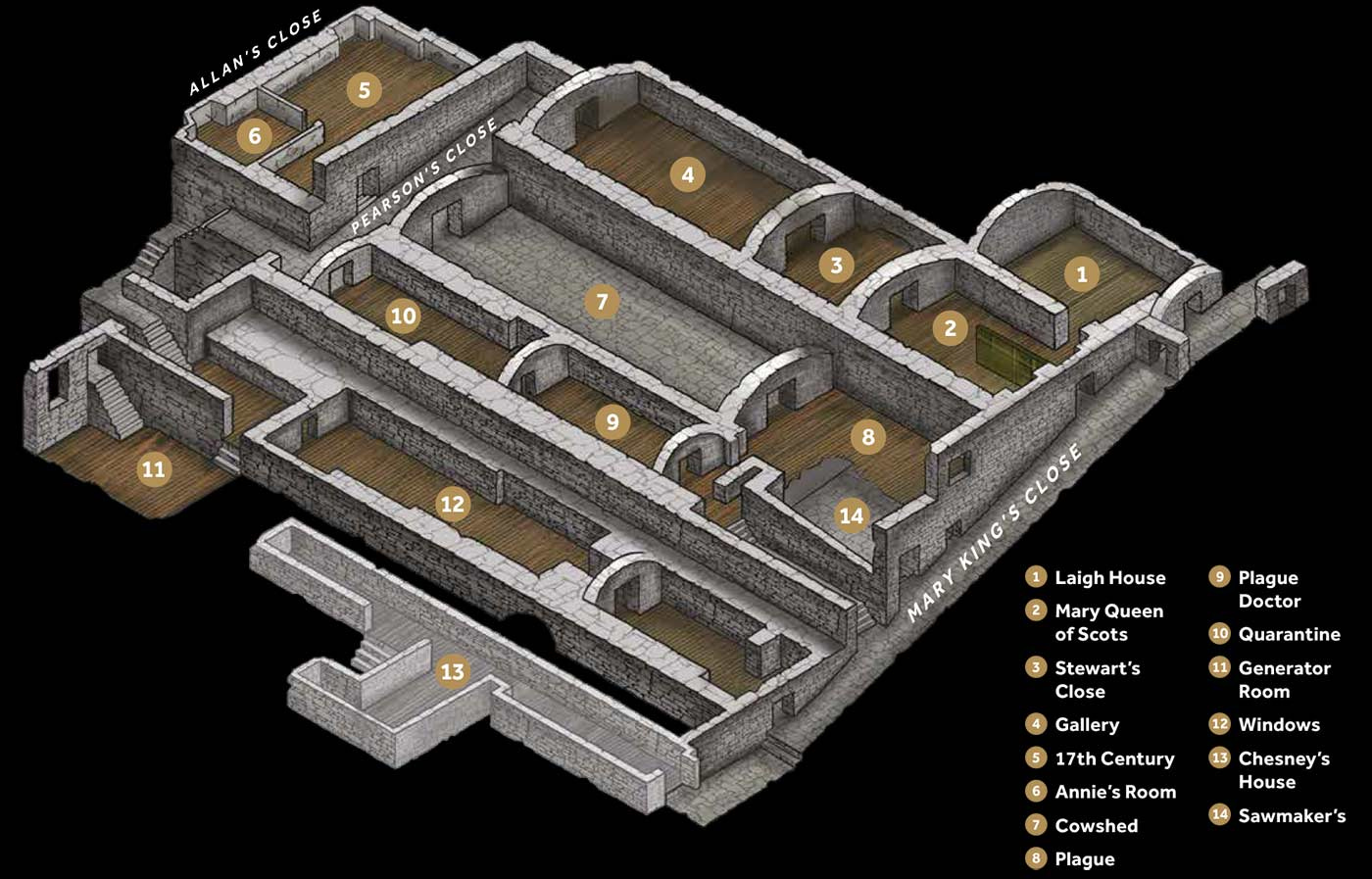

From their website, a map showing the size of the close and the adjoining buildings/rooms. All of this is now covered over. The Cockburn street door from where I entered in primary school is at the bottom of the close. The top door leads to the High Street.

By the 18th century, the Act of Union with England had been established, and there was no need to keep building inside the city walls. Gradually, Edinburgh spread out into the ‘New Town’, an impressive Georgian project which turned Edinburgh into a sophisticated and modern capital. The Nor Loch was drained, and the city became a popular tourist destination (that hasn’t changed). It even came to be known as the ‘Athens of the North’. Having never visited actual Athens, I can’t tell you how accurate this is, but I suspect Greece is a lot less chilly and grey.

Carlton Hill’s classical style New Town buildings helped cement Edinburgh’s new reputation as a beautiful and classy city.

And so, the Old Town fell into a state of disrepair. It was not subjected to the modernisation of the New Town, and became the haunt of much of Edinburgh’s poorest, including Irish and Highland immigrants. It garnered a seedy reputation for crime, sex work and the night time activities of body snatchers like Burke and Hare. In this unstable and unsafe warren of crumbling buildings, fires were common, as were accidental deaths. The poor crowded into the ‘vaults’, a series of storage rooms built into the new South Bridge, and overcrowding and unsanitary conditions were rife. In fact, the Old Town’s unfashionable reputation remained until all the way into the mid 20th century - my high school music teacher, who grew up on the High Street, told me it was akin to a scheme (council estate) in terms of reputation. Now, of course, it’s insanely popular as a tourist destination, although in my mind its never quite shaken its slightly run-down vibe - perhaps due to the overwhelming amount of tacky, rather depressing tat shops it harbours. Although where else can you get your Princess Diana Memorial Tartan? (Tourists please note: buying a see you Jimmy hat with fake ginger hair is a hate crime, and if I see you in one, I will slap if off your head).

Mary King’s Close was essentially forgotten, until building work in the 1930s unearthed many of the lost rooms of the Close.

NB: It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when people stopped living in the Close - some sources claim it was buried and forgotten after the Chambers were built, but there are records of people hanging out in pubs in or near the Close in the 18th century, as well as a resident being there as late as 1901. As far as I can tell, the Close was no longer permanently inhabited after the 1760s, but traders continued to use the workshops there until the end of the 19th century, when only one craftsman, the sawmaker Andrew Chesney, remained.

What was found was essentially a moment frozen in time - belongings, tools and personal items from the 17th century - even wallpaper - still remained in the Close. Fascination grew and eventually it was opened as a tourist attraction in 2003, only a few years after my school visit. I wish now that I’d been able to appreciate just how special and significant our visit to this truly unique place had been.

So…what of the ghosts?

In the years after Mary King’s Close was abandoned, it gained a reputation as haunted. Most of these ghost stories, including the ones I mentioned at the beginning, have vague and somewhat mythical origins.

One of the sources for the ghost tales of Mary King’s Close is George Sinclair’s succinctly titled Satan’s Invisible World Discovered: Or, a choice collection of modern relations, proving evidently, against the atheists of this present age, that there are Devils, Spirits, Witches, and Apparitions, From authentic Records, and Attestations of Witnesses

of undoubted veracity. That’s right, it’s another spooky pamphlet with an overlong title; I just can’t get enough.

Sinclair (1630-196) is described by Wikipedia as ‘a mathematician, engineer and demonologist’ which tells you all you need to know about science in the 17th century. Satan’s Invisible World is less a treatise on the realities of belief and spiritualism and more a bumper book of ghost stories, one of which was told to me as a child in the very room it supposedly occurred.

According to Sinclair, a Thomas Coltheart and his wife were preparing to move into the close (presumably at some point in the 17th century) when their maid was spooked by a friend who told her that if they did move to the close they would have ‘More company than yourselves’.

On their first night in the close, the Colthearts were reading (the Bible, obv) in bed, when Mrs. Coltheart glanced up and saw the disembodied head of a man floating in front of the fire place. This was followed by ‘a young child, with a coat upon it, hanging near to the old man’s head’ and the couple immediately leapt out of bed and started to pray.

Praying didn’t seem to help - the next thing to materialise was an arm, attached to nothing, which only heightened their fear. The arm itself, however, was friendly; it attempted more than once to shake hands with Coltheart, who apparently declined. Fair enough.

The most remarkable part of the tale is skipped over - after these disembodied apparitions, there comes the groans of a dying man, and then Sinclair goes to on say that the hallway outside their bedroom was ‘full of small little creatures dancing prettily; unto which none of them could give a name, as having never in nature seen the like.’ Sinclair doesn’t bother to describe the creatures in any way, and so they remain a tantalising mystery.

The Coltheart’s remained in the house until Mr Coltheart died a short while later, confident to their last that God would protect them from whatever the hell was happening.

As with the pamphlet on the Mackie Poltergeist, which I explored in an earlier article, the aim of this gruesome tale seems to be to convince the belief both in the existence of spectres and the power of God. Some context was also added to the story when it was retold to me as a child: the body parts, as I mentioned earlier, where those of plague victims of the Close, who had been chopped into pieces to make for an easier removal. Gross.

Other, less fleshed-out (pun intended) stories about the Close include Andrew Chesney, the last resident in the Close, who was forced out by the council in 1901 - yup, in the 20th century. His disgruntled ghost is supposed to haunt the Close, presumably to complain about council tax rates. There’s also a classic Woman in Black, who is said to scratch visitors with unseen hands.

‘Annie’s doll’ is probably the story with the most recent origins. In the 1990s, Japanese psychic Aiko Gibo visited the Close and claimed she had connected with the ghost of a child, Annie, who had lost her doll and was upset. Aiko went out to the nearest shop and bought Annie a tartan-clad Barbie, which seemed to appease her, and to this day, people leave dolls and toys in the location known as ‘Annie’s Room’ within the Close. I distinctly remember being in this room as a kid, with no lights except our guide’s torch, and the odd sight of a pile of dusty dolls and teddy bears piled in the corner.

Personally, I’m not particularly interested in Annie’s story. I’m always a little sceptical when a medium shows up and declares a ghost- with no previous legend - to exist. So far no records have turned up an ‘Annie’ living in the Close. Plus there is something weirdly morbid about the heap of toys and dolls that has accumulated over the years. And I can’t help thinking about the vulnerable children of Edinburgh who might have appreciated those toys more than a ghost - you can donate toys to Edinburgh’s children’s hospital here, for instance.

Mary King’s Close, unlike most of the ghost stories I’ve covered in this series, is less a tale that reflects the fears of contemporary readers, and more a warning from the past. It’s literal status as buried history reminds residents and tourists alike of the horrors of poverty and the past, and suggests there was something base and animalistic about the way our ancestors lived that we have somehow evolved out of. Of course, this isn’t true - the inhabitants of Mary King’s Close were simply the victims of something scarier than ghosts - poverty.

If you liked reading about Mary King’s Close and its history, the good news is that my Fringe venue is only a 4 min walk away, on the other side of the Mile, in another set of underground rooms.

And if you want to hear me talk more about Mary King’s Close, I was a guest on the Loreman Podcast recently, which coincidentally focused on the Close the very same week I wrote this article! Spooky!

Thank you for going on this haunted journey with me - I’ve really enjoyed getting the chance to write and research all of these favourite stories from my childhood!

Liked this? Support me on with the price of a coffee here or buy a ticket to Haunted House!